Generally, “February” and “Wildcat Canyon” are not words you hear in the same sentence around southwest Utah, except for maybe in this sentiment: “Wildcat Canyon? You can’t hike there in February. There’s too much snow!” Or perhaps in this little nugget: “Wildcat Canyon? On the Kolob Terrace road? You need a snowmobile to get up there!”

|

| No snow on the Kolob Terrace Road in February? |

Ordinarily you would. Yes indeed, you would need at least a snowmobile, and probably snowshoes, or skis, and several layers of warm winter clothing and while you were up there you would need a large pile of wood for your fireplace. However, until the week following our hike, temperatures have been above normal and there has been very little snow in the higher elevations of Zion National Park. The elevation of the Wildcat Canyon trail is around 7000 ft above sea level. There should be snow in February! But there wasn’t, so my friends and I decided to take advantage of this alternate opportunity. We left our skis in the garage, packed some lunch, laced up our hiking boots, and took the scenic route up to the high country.

|

| Cinder cones pepper the landscape in Zion |

A pair of speed limit–oblivious mini-coopers careened past us on the twisting drive up the Terrace road, but thankfully they did not turn off at the trailhead. Good riddance! We had the Park to ourselves, and this trail is one of the best. There is little elevation gain or loss as it weaves through the mature forest of Ponderosa pine. Over the course of the day the temperature never rose above 50°F, and the sun played hide and seek behind the clouds and between the trees, but there was no wind to chill us and so we were comfortable, even when we stopped for views or a snack.

|

| Ponderosa pine forest |

|

| Ponderosa pines reach for the sky |

The Wildcat Canyon trail is the starting point for The Subway, one of Zion’s premier hikes. Nowadays you need a permit for even a day hike, but when I did the daytime deed back in the summer of 1991 it was not required. Today we had neither intention nor permit to hike The Subway (What? In this weather? Are you crazy? It’s February, for crying out loud!). We merely took the short spur out to the overlook above Russell Gulch.

|

| The Subway route |

|

| Cathy absorbs the scenery |

|

| John takes more photos than I do |

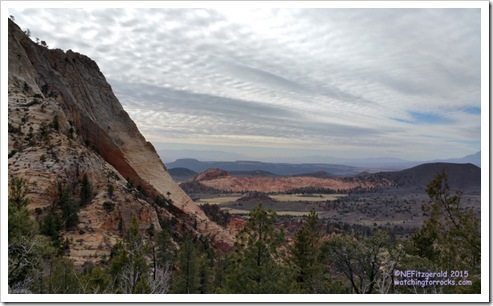

We were surrounded by the massive Navajo Sandstone, 2000 feet thick in places, the fossilized remnant of a vast sand dune desert that existed for nearly ten million years, from around 190 to 180 million years ago in the Early Jurassic period. Along the top where we perched and photographed is the J-1 unconformity, a beveled surface, a respite from desert conditions, upon which a rising shallow sea briefly covered the dunes. This sea left behind the red mudstones of the lower Temple Cap Formation. Above this thinner layer of red rock, desert conditions are evident once again in the fossilized wind–blown sand that once shifted on a coastal dune field.

|

| Temple Cap and Carmel Formations top the massive Navajo Sandstone |

But like the Navajo Sandstone, over time these Temple Cap sediments were beveled. Subduction of the Farallon oceanic plate to the west created the crustal compressional features of the Sevier Orogeny. The uppermost rock layers seen from the overlook are part of the Carmel Formation, limestones and sandstones deposited in the shallow inland sea of a “back bulge basin” that came into existence around 170 million years ago because of this compression.

|

| Fine fractures in a sandstone cobble |

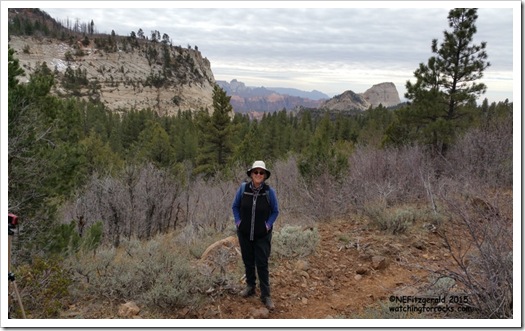

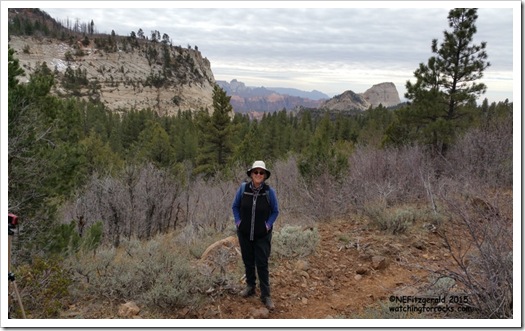

We followed the meandering trail until the views opened up along one side of Wildcat Canyon. The gray scrub shrubbery of Gambel oak lined the trail, and I remembered how these barren branches of winter changed with the seasons and how their leaves blazed orange gold in the September sunshine.

|

| Enjoying February |

A less than impressive patch of snow appeared after around two miles, so we made this our turnaround point and found some lunch logs where we perched once again.

|

| Keep moving. Not much snow to see here! |

Nestled on the eroding western edge of the Colorado Plateau, Zion is awash in faults and fractures. Many areas are also covered with basalt flows and peppered with cinder cones. The basalts along the Wildcat Canyon trail are mapped as “Qv” (Quaternary volcanics). According to the explanation on the geologic map of Zion, these rocks are from “basalt flows and cinder cones; the former occupying canyons and structural benches and in many cases capping mesas. Cinder cones are associated with normal faults…Dated basalts range in age from approximately 0.26 to 1.4 million years before present.”

|

| Basalt takes a hit from gravity |

|

| Basalt flow on the Wildcat Canyon trail |

We spotted some poop on a rock and paused to ponder the package. Coyote? Probably. Fox? Possibly. Wolverine? Not likely, but we could always hope.

|

| Someone else has walked this way |

Soon we sauntered out of the trees and were back at the car. The light had changed again – clouds that had not been there earlier in the day were now splattered across the sky, thin layers exploding from some unseen point beyond the western horizon. Standing there in the panorama, we treated ourselves to a post-hike early Easter delicacy.