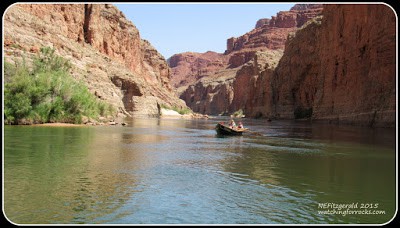

Departing South Canyon, our guides deftly maneuver the rafts ever-so-carefully backwards, away from the beach and into the main channel. We happily avoid crashing into and sinking the flotilla of dainty dories that has stealthily crept up behind us. We cheer, wave, and point our behemoth boats downstream, leaving the dory riders to make their own discoveries amid the South Canyon ruins. It is mid-morning of our first full day rafting on the Colorado River in Grand Canyon. I am beside myself with enthusiasm, thrilled that there is room on the raft for both of me.

Dories incoming! (click on any pix to enlargenate)

At this point the canyon takes a wide swing to the left, the entrenched meandering river carving deeper and deeper into the older, lower layers of the Redwall Limestone, exposing its many caves. You could swing a cat right now and it would easily land inside the darkness of Stanton’s Cave. Swing a bit harder and it would land in the lushness of Vasey’s Paradise. Swing really hard and that kitty just might find itself paws down on the soft sand at Redwall Cavern, about a river mile and a half downstream.

I think that’s Stanton’s Cave on the lower right

Stanton’s Cave was named for Robert Brewster Stanton. He was chief engineer of an expedition in 1889-1890, optimistically surveying the Grand Canyon for a possible water-level railroad line through the pre-Glen Canyon dam canyon. He used the cave to cache supplies. Archaeological materials found here, mostly in the form of split-twig figurines, have been dated to between 3000 and 4000 years ago. Pleistocene vertebrate remains have also been excavated in the cave. Today the cave is closed to the curious public due to its being an important female bat-roosting area, particularly Townsend’s big-eared bats. For more info on the bats, check out the web reference below for the cave.

Coming up on Vasey’s Paradise

Vasey’s Paradise is a groundwater channel in the Mooney Falls Member of the Redwall Limestone. It was named by John Wesley Powell in honor of botanist George Vasey. Vasey accompanied Powell on his 1868 “Rocky Mountain Scientific Exploring Expedition” but was not a member of the party when Powell took his famous first ride down the river in 1869. Click the link below for more info on Vasey’s Paradise.

Vasey’s Paradise

Vasey’s Paradise

We are still in the Redwall Limestone, but the rocks, they are a-changing. Not-so-subtle differences display themselves at river level. So… although Vasey’s Paradise flows through the Mooney Falls Member, it is up there on the cliffs. Now, in the older rocks at river level, it is a different story. The distinctively banded Thunder Springs Member has appeared, and it’s impressive.

Thunder Springs Member, Redwall Limestone

Chert/carbonate banding is distinctive and not a bit overwhelming

Thunder Springs Member – impressive among superlatives

In a world of superlatives that define Grand Canyon geology, the Thunder Springs Member of the Redwall Limestone is up there with the best of them. In speechless silence we float through this straight stretch of canyon, each of us lost in thought, overwhelmed by the beauty and mystery and absolute presence of these banded layers.

The seas come in, the seas go out. The rocks of the Redwall tell the story of two key episodes of the transgression (advance) and regression (retreat) of a shallow sea 340 million years ago. The Thunder Springs rocks are part of this story. Its sediments were deposited as the sea retreated off the continent, becoming more and more shallow as geologic time passed. The banded appearance is due to alternating layers of dark reddish brown or dark gray silica (chert) and light gray carbonates (limestone or dolostone).

I can’t help myself. I either must press the video button on my camera or I will fall out of the boat gawking:

Another bend in the river brings us to a large natural amphitheater named Redwall Cavern. On his first (1869) expedition down the river, Major Powell had this to say:

August 8: “The water sweeps rapidly in this elbow of river, and has cut its way under the rock, excavating a vast half-circular chamber, which, if utilized for a theater, would give sitting to 50,000 people. Objection might be raised against it, however, for at high water the floor is covered with a raging flood.” (quote courtesy PBS).

Redwall Cavern

The familiar chert/carbonate banding is clearly visible. We are still within the Thunder Springs Member. We disembark onto the soft sand and have a look around.

Hitting the sand at Redwall Cavern

Rafting buddy Kris investigates the bands

I love this place and everything about it!

Jay the guide points across the river to a rounded structure at river level. It is a bioherm, a mound or dome-shaped mass of rock composed of the calcareous (shell) remains of sedentary shallow-ocean organisms such as corals, algae, gastropods, mollusks, and the like. The bioherms are generally surrounded by a different kind of rock (for example, a non-reef limestone). I vaguely wonder what the correlation might be, if any, with the cavern – they both have a similarly rounded shape (although the cavern is much larger?), both are at water level, both are within the same member of the Redwall. Hmmm… The bioherm looks quite substantial, actually, once you stare at it long enough. Which is what I do while Kris examines some banding.

A bioherm

Bioherm close-up

I continue lollygagging at the cavern’s edge, and soon notice that everyone, even Kris, is back on the boat, patiently waiting for me to finish staring at the bioherm. I scamper over the rocks, hoist myself on board with all the grace I can muster, and we push off once more. We are leaving the Redwall. It’s been fun! However, it is time for the Cambrian Muav Limestone to put in an appearance. It’s over there at river level, just beyond the bioherm and beneath the Bridge of Sighs.