It was a crisp October morning as we zipped up Cedar Mountain in our three–car caravan, bound for an eight–mile hike around Navajo Lake and along the Virgin River rim trail. Interspersed with the grayed skeletal remains of Engelmann spruce (victims of an endemic beetle population and a dubious forest management policy of the past century), the aspen leaves blazed their burnt red–orange and golden yellow brilliance against a cloudless sapphire sky. As we cruised I noticed orange–vested people near the side of the road, parked in camp chairs and peering through binoculars across the meadows. A suspicious little voice inside my head told me they were probably not just admiring the leaves.

According to the chatty forest service volunteer at the trailhead, today was the first day of elk hunting season. Oh yeah…it was the first weekend in October! I surveyed his orange vest, thoughtfully considered my tanly attired friends, and wondered who would likely be the sitting hiking target. I, on the on other hand, was flamboyantly garbed in a blue hat and pink shirt and so could hardly be mistaken for a four–legged wapiti. Someone might mistake me for a tree in autumn splendor, though. I was willing to take that chance.

|

| Barbara has pink fluff in her hat so won’t be mistaken for an elk. |

|

| If you hike during hunting season, in lieu of an orange vest , wear pink! |

Navajo Lake has its own unique history here in the volcanic high plateau country of southwest Utah. Around 58,000 years ago, basalt lava flows erupted from some 20 different vents not far to the northeast. Cinder cones mark the source of these many flows in an area called Henrie Knolls. Oozing its way across the broad plateau landscape, the southernmost flow blocked the drainage of a small, narrow creek, and Navajo Lake was born.

|

| Basalt flow at Navajo Lake in southern Utah |

The 58,000 year old lava flows rest unconformably upon the freshwater limestones, sandstones, and conglomerates of the 50–million year old Claron Formation. Over time, as rain and snowmelt percolated down through the basalt it dissolved this Claron limestone beneath it and formed sinkholes and caves. One of these sinks drains towards the precipitous edge of the Markagunt Plateau and feeds Cascade Falls, the headwaters of the North Fork of the Virgin River.

|

| Aspen leaves |

Navajo Lake is quite shallow, somewhere around 25 feet deep. It is fed by abundant springs that are probably recharged by rain and snowmelt flowing into sinkholes in nearby valleys that are themselves covered by basalt flows. In the 1930s, an earthen dike was constructed to maintain a constant water level in the lake. Since the sinks at Navajo Lake are located mainly at the northeast end, this dike also prevents the lake from draining completely into the sinks, especially during dry years.

|

| The earthen dike was constructed in the 1930s. Sinks are in the dry area. |

At first, the trail winds in and out of aspen groves along the lake’s northern shoreline. It then contours gracefully along the jagged edge of the basalt flow at the northeast end of the lake. Unsuccessful attempts were made to find olivine crystals in the basalt boulders, a rather difficult endeavor as I scurried along to keep up with the other hikers who were waaaay ahead of me by this time.

|

| Signs do not lie. |

|

| The trail weaves its way through the basalt field. |

|

| View from basalt field, across area of sinks. Earthen dike holds back water. |

Soon it was time to climb out of the valley and onto the rim of the plateau. Navajo Lake sits at around 9000 feet above sea level. Via the dike trail segment of our route (which is a bit too far from the dike to be called the dike trail, in my opinion) the elevation gain is around 500 feet in what seemed to me to be ten miles but was most likely only one or two. I lost count of how many switchbacks there were – if I had counted them all I probably would have fainted at the number. I just kept putting one foot in front of the other, up, up, up the steep trail through the conifer forest until I saw daylight and not dirt in front of my nose.

|

| Finally! The rim! |

Since everyone preferred to reach the top before stopping, our lunch–with–a–view occurred at 2:00pm, probably setting a hiking club record for late dining.

|

| Lunch with a view is always nice, no matter the hour. |

The trail threaded its way along the rim high and level for a mile or so, taking us east along the edge of the Markagunt Plateau. The views were worth every knee crunching, lung busting, gasping–for–pesky–oxygen–molecules step up those switchbacks.

|

| The edge of the Markagunt Plateau |

|

| Aspens |

|

| Standing at the edge of the Markagunt Plateau |

Soon we were on our way down, down, down through the trees one last time, to the trailhead for Cascade Falls where we had left a shuttle car. As the others traded boots for sandals and prepared to head home, I took the opportunity to scamper over to the falls.

|

| This way to Cascade Falls |

|

| The trail winds along the edge. |

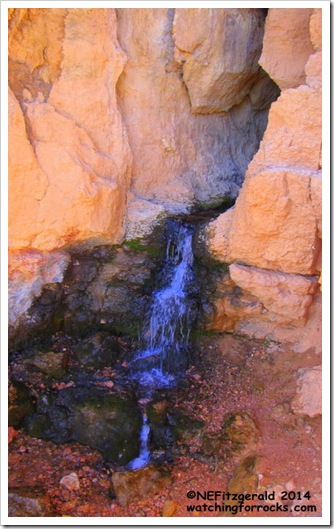

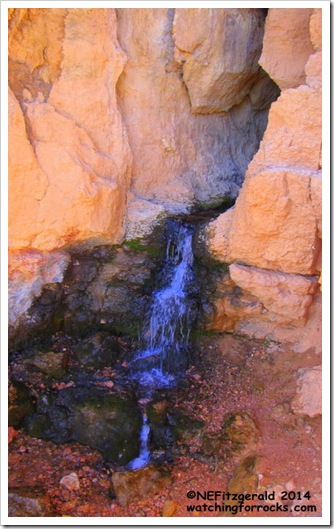

This section of trail is often closed due to wash out for the same reason that the sinkholes and caves exist – the dissolution of the water–soluble limestones of the Claron Formation. Footing became particularly squirrelly nearer to the falls itself, with water seeping here and there from cracks and crevices, the hillsides tumbling in a gravity–assisted frenzy of red, yellow, orange, and white boulders.

|

| The headwaters of the North Fork of the Virgin River |

|

| Cascade Falls comes out of a limestone cave |

Depending on recent precipitation this underground river can be a trickle or a torrent. I took a few moments on the viewing platform to pause and ponder this four–foot high dribble of water and its journey underground, and considered how this seemingly innocuous flow could eventually carve such a dramatic scene as that found in Zion Canyon. I knew my fellow hikers were waiting patiently so I did not linger much longer. I stepped away from the falls and onto the squirrelly trail, back to the cars and those tan–garbed friends who thankfully had not been mistaken for elk.