Southern Utah displays some of the world’s most spectacularly in–your–face geology. It is so in your face and on display that it could practically ring your doorbell, invite itself in, pour itself something to drink, and stand in your kitchen with the refrigerator door open while looking for a snack.

|

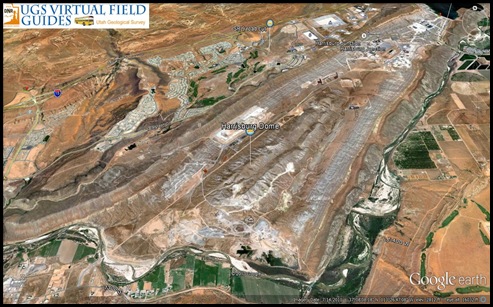

| View eastward across Harrisburg Dome |

On a recent morning hike just a few miles from my back door I found myself overlooking an area of the county that, as a geology student in the final weeks of field school, I had mapped back in the summer of 2009.

The view was towards the east across the Harrisburg Dome (at least what’s left of it), so named for the Harrisburg member of the Late Permian Kaibab Formation that is exposed in the center or core of this geologic structure. The gypsum–rich and limestone deposits of the Harrisburg member were deposited in a shallow sea around 250 million years ago. Overlying it are the younger, weak bedding planes of the Moenkopi Formation – a thousand feet or more of mudstones, siltstones, shales and gypsum evaporites.

|

| Yellow lines indicate the outer ridges of the elongated dome – view eastward |

The elongated dome is an extension of the Virgin anticline, a distinctive upward fold in the Earth’s crust that, in the case of southern Utah, is a result of tectonic compression from the west.

|

|||||

| Google Earth northward view of Harrisburg Dome, (courtesy Utah Geological Survey) |

Starting around 140 million years ago and encompassing a time span of nearly 100 million years, no event left more of a widespread effect on the Utah landscape than the Sevier Orogeny. Over millions of years, tectonic compression from the west squeezed and crunched the eastern Great Basin landscape, shortening the crust by perhaps 100 miles and elevating it into some serious mountain terrains, which even as they rose were eroding away, grain by grain.

|

| Dashed yellow line shows what might have been, in the center of the dome |

Shortening of the Earth’s crust has been attributed to subduction of the Farallon oceanic plate beneath the west coast of North America. One hundred fifty million years ago the edge of the continental plate was western Nevada. Like a throw rug pushed, folded, and crumpled over a hardwood floor, western Utah was thrust upwards, faulted, folded and buckled into the high mountain ranges and eroded hills we see today.

|

| Field school cross section view of dome – note dashed lines (the yellow dashes of previous image) |

Within an anticline the older rocks are found in the core or center. Over time this core is eroded away, exposing younger and younger uplifted rocks that are exposed in the remaining arms or limbs of the dome. The further out you go from the core, the younger the rocks become. The angle of tilting of the beds indicates what direction the rocks were folded – up, or down. In a syncline, the rocks tilt inward and so the younger rocks are found in the center and get older as you move outward.

In trying to understand a feature on the ground like the Harrisburg Dome (or anything else geologic, for that matter), we attempt to recognize what isn’t there anymore. In a place like southern Utah, that recognition can certainly involve pushing a lot of rugs across the floor and answering a lot of doorbells.