You just never know what you’ll discover when you walk in to the Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm in St. George, Utah. I volunteer at the museum lab there in the winter, and have occasionally written about fun with the Farm (such as here and here). Usually I just walk directly back to the lab, bypassing the extensive display of trackways. But one day a few weeks ago I decided to spend some quality time walking around and investigating the exhibits. Hey, I’m a volunteer. I can do whatever I want!

|

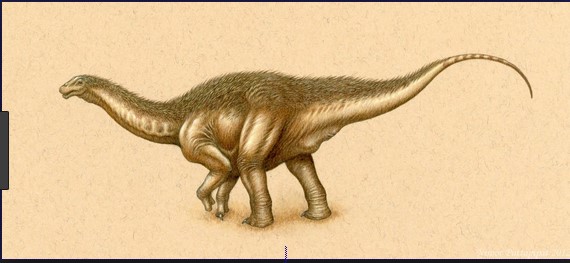

| Apatosaurus |

There is a small 550–square foot exhibit room so I moseyed in there. This past summer the museum staff had assembled what they referred to as a “low budget display.” But as I glanced around the room, my jaw immediately dropped. In glass cases along the walls were examples of exquisitely constructed origami dinosaurs, each folded by one clever and talented person using mainly one sheet of paper.

|

| Simple models using one sheet of paper |

Jerry Harris is the director of paleontology at Dixie State College in St. George and is a Discovery Site Foundation trustee. He has been doing origami literally since he was “in” high school; one memorable English teacher crumpled up a term paper Jerry had submitted, threw it at him while reprimanding him to “stop folding paper in class!” His Dad had tons of books about origami, and so Jerry used these books and their examples to teach himself the art.

|

| Sauropods |

All models in the exhibit were folded by Jerry, who also invented the folding process for five of the models. He didn’t invent the models on a computer as some people do – he just experimented with the paper. He has been doing this long enough to have an innate understanding of basic folding techniques and so is able to conjure a mental image of what the model should look like as the folding progresses.

|

| Tyrannosaurus |

The completion process for many of these models can take many days. The folding itself may take only a few hours, but there is a need to get the paper wet along certain crease lines and clamp it in position. Only after a particular crease dries does the folding process continue. Often there would be several models in progress at once, in various stages of completion.

|

| Triceratops |

Over the years much experimentation has been done on different paper types in order to fold and hold a fold. A sheet of paper is first prepared with a methylcellulose solution – this gives the paper ‘sizing” which in turn gives it the proper strength. When he needs to make a crease or have the paper hold a certain shape, Jerry wets the paper along the crease – this re-dissolves the methylcellulose and makes the paper more pliable. The crease or shape is then formed and clamped – as the water dries, the methylcellulose re-solidifies to hold the shape.

|

| Mymoorapelta |

Early simple traditional models of ancient China and Japan involved coarse and expensive paper. These models were largely ritualistic while being less artistic and scientific than the models of today. It wasn’t until the late 1960’s that more sophisticated folding techniques began to be explored. Paper specifically designed for origami also became more available.

|

| Woolly Mammoth |

Today, a newer and better understanding of folding techniques coupled with a much wider diversity of paper types has led to complex models that previously would have been impossible to create with a single piece of paper. However, despite the discovery of origami techniques that can produce a quite large number of points from a single sheet of paper, no one has yet been able to produce as many points as needed for a skeleton from a single sheet. “Compound origami” consists of multiple sheets of paper that fit together.

|

| Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops skeletons require multiple sheets of paper to construct |

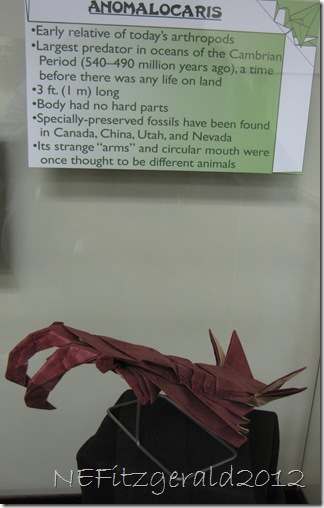

Hey! How did these two critters get in here? They’re not dinosaurs!

|

| Anomalocaris from an ancient sea |

|

| Trilobite from an ancient sea |

The exhibit is scheduled to be on display until early February. There is talk of possibly making it a traveling exhibit.