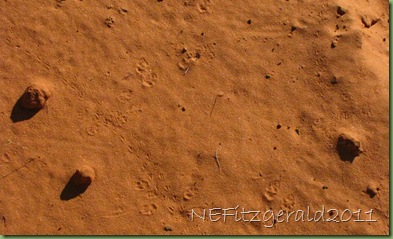

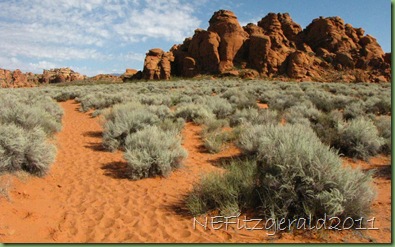

This week I took a leisurely walk in the Red Cliffs Desert Reserve near my home in southwestern Utah and noticed scores of small animal tracks that had been imprinted that very morning. The next day I stood staring in amazement at a trace of small animal tracks in the red rock sandy siltstone that had been imprinted nearly 200 million years earlier.

I have been volunteering with the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm (click here and here) for the past couple of winters. Usually I work in the lab on fossil fish, viewing the sample through a microscope and picking away the sandy silty matrix with a carbide–tipped hand tool.

But last week the oldest known Lower Jurassic Moenave fossil locality in Washington County needed our attention. Andrew Milner, dinosaur site paleontologist, put out a call for help. He would be leading a field trip to the site this weekend with the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology. Sadly, a significant amount of garbage had been dumped into the canyon over the past year, and he hoped the area could look clean and spiffy. So on a chilly, windy late–October morning the gaggle of usual suspects gathered with buckets and gloves and pick–up trucks, ready to haul out as much trash as we could manage.

|

| Volunteers clean up the canyon |

|

| Melinda carries it out |

|

| Linda ready to move some trash |

|

| Loading up the trash |

|

| Thanks, Volunteers! |

Trackways have been and continue to be discovered all over Washington County. The small four–toed footprint is believed to be Batrachopus, made by an early crocodile relative such as Protosuchus. As you can see from the photo, these footprints are tiny! Unless you know what you are looking for, they are easily overlooked. In addition, these croc–like critters walked on all fours and their back foot often stepped where their front foot had been, “overprinting” the front print and obscuring it. These (even) smaller front prints can be found but are not as common as the back print.

|

|

Batrachopus – gloved finger for scale |

The larger prints are Grallator, made by a small meat–eating dinosaur and much easier to distinguish in the surrounding rock.

|

|

Grallator – booted feet for scale |

Anhydrites and other evaporites from the underlying Chinle Formation up through Dinosaur Canyon member of the lower Moenave indicate that dry, arid conditions prevailed. But as time went on the environment became wetter and less arid. The early environment where these animals thrived was much different from the Utah of today. Geological evidence shows that it was a shallow, flat–lying meandering river system. Currents would have flowed from the southeast towards the northwest, from mountains in what is now Texas into a low–relief landscape of an ancient Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming.

Moving up–section through the Dinosaur Canyon member to the Whitmore Point member of the Moenave we see evidence of a large freshwater lake now known as Lake Dixie. It was along the edges of this vast inland body of water that our early meat–eating dinosaurs and crocodile relatives walked, leaving proof of their existence for us to discover in the red rock canyons of southern Utah.

|

| Andrew points out Chinle/Moenave contact |

|

| Peering up into the Moenave |

|

|

Grallator ( and Batrachopus (r) |

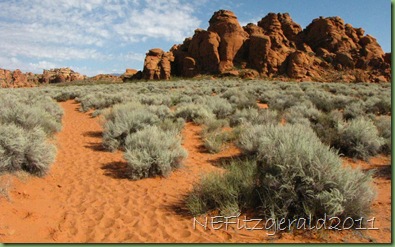

On the Chuckwalla Trail in the Red Cliffs Desert Reserve of southwest Utah…

…we see fleeting evidence of tiny critters that skittered this way before us…

…just as those coming later see evidence of our passage…

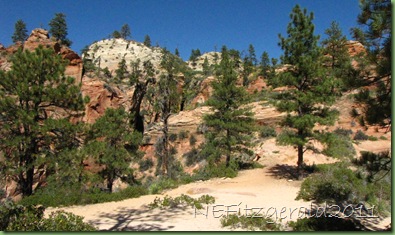

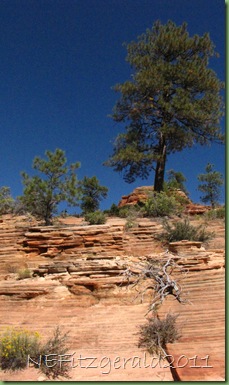

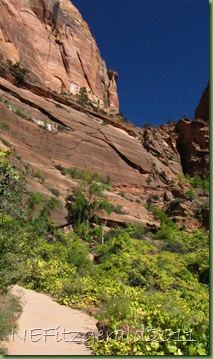

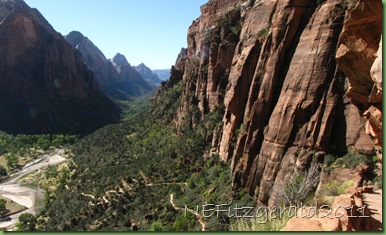

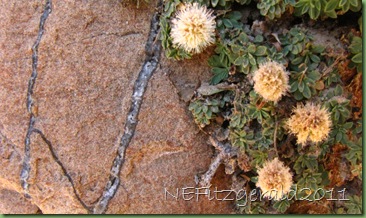

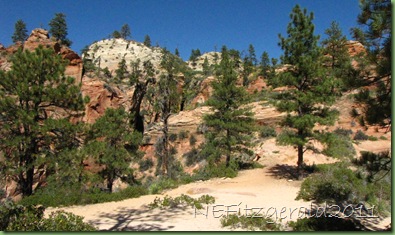

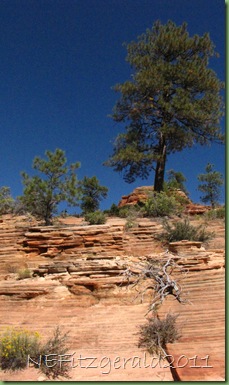

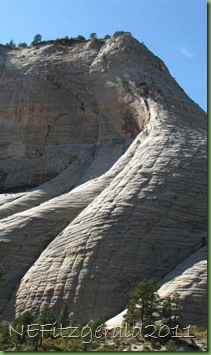

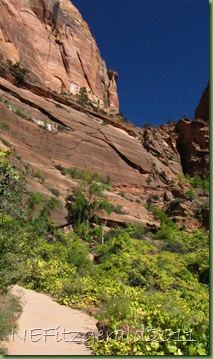

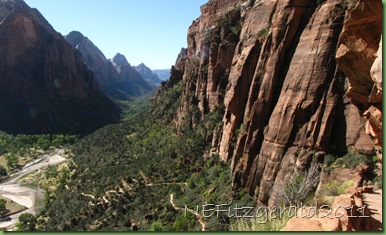

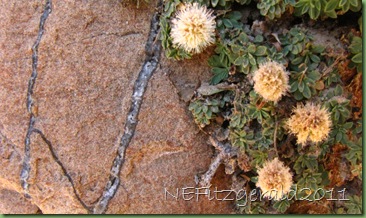

Life grabs hold where it can in Zion National Park, in the shadowy crevasses of the bleached–white cliffs and desert varnish–streaked walls of Navajo Sandstone, here and there dotted with aromatic ponderosa pine, gnarly Utah juniper, and lingering high–desert wildflowers. An unhurried ramble past Scout’s Lookout on the West Rim trail offers anyone who is interested a first-rate display of this resolute late–October life.

Life grabs hold where it can in Zion National Park, in the shadowy crevasses of the bleached–white cliffs and desert varnish–streaked walls of Navajo Sandstone, here and there dotted with aromatic ponderosa pine, gnarly Utah juniper, and lingering high–desert wildflowers. An unhurried ramble past Scout’s Lookout on the West Rim trail offers anyone who is interested a first-rate display of this resolute late–October life.

|

| West Rim trail weaves across Navajo Sandstone |

|

| Life clings to the rocks |

|

| Virgin River cuts deep in Zion Canyon |

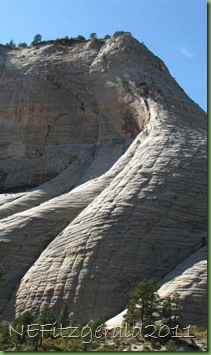

Fluted fossilized dunes drift down from the sky and drape themselves gracefully hundreds of feet above the trail.

|

| Fluted Navajo Sandstone sculpture |

Junipers tenaciously choreograph their roots through the cracks and joints of weathering sandstone.

One way or another, life survives and thrives in this arid wilderness of sculpted rock.

The trail, carved into solid sandstone, meanders further into the backcountry and soon will start its climb to even higher reaches of the park.

|

| West Rim trail snakes through Navajo Sandstone |

|

| West Rim trail ascends to rim of sandstone cliffs |

Every time I come to Zion I am awed and not a little overwhelmed by these towering sandstone cliffs, fossil remnants of a dune field that existed for some 10 million years during the Early Jurassic. In the sculptured cross–bedding of these ancient dunes we behold mere moments in time and space, a quick snapshot of events that occurred almost beyond the grasp of our imaginations. We study the rocks and try to understand them, of course, piecing together our interpretations bit by bit. That is what geologists do.

But this is Zion, one of the most unique landscapes on planet Earth. Its mystique will never be totally explained, even though science allows us astonishing glimpses into its history. The mystery and enchantment of these ancient rocks will remain. And at the end of the day, how could it be otherwise?Southern Utah has got to be one of the most extraordinary places in which to live. Easy access to Zion National Park is without a doubt a major reason. There are hundreds of miles of trails in the park; hiking any of them is worth the 45–mile drive from St. George.

|

| Bridge across Virgin River near the Grotto |

One of my favorite areas in Zion (ok – they are all my favorite areas, I admit it) is the West Rim trail. You can start from the top or you can start from the bottom, but if you hike the entire length you’ll be pounding your knees on nearly 14 stunningly scenic miles of unforgiving Navajo Sandstone slickrock. You’ll want some serious anti–inflammatories on board, plus you’ll need to spot a car at one end.

None of these options fits my plan for the afternoon, however. My choice is a six–ish or seven–ish mile, out–and–back hike to a lovely bridge across a small canyon hidden in the heights of blindingly white sandstone. The trail ascends gradually from the Grotto across loose talus slopes of silty–sandy Kayenta Formation. It continues relentlessly up, up, up until reaching the massive streaked cliffs of Navajo Sandstone.

|

| West Rim trail |

|

| West Rim trail ascends talus slope of Kayenta Formation |

|

| Opalized silica fills fractures |

|

| Opalized silica fills fractures in Navajo Sandstone |

Once past the gaggles of holiday hikers chattering their way through Refrigerator Canyon, up Walter’s Wiggles to Angel’s Landing and on to Scout’s Lookout, I finally have the trail to myself.

|

| Refrigerator Canyon |

|

| Walter’s Wiggles are cut into Navajo Sandstone |

In the next post we’ll continue to the bridge, high above Zion in the Navajo Sandstone.

I hope you’ll re–fuel and join me!

|

| Just beyond Scout’s Lookout – sandwich with a view |

The summer season of my Yellowstone interpretive park rangerosity has come and gone, but the memory of our fun, fishy final backpack to the Shoshone Lake patrol cabin remains to be savored – especially the recollection of that newly–hooked brown trout sizzling spicily on a propane stove.

Oh, yeah. Talk about tasty!

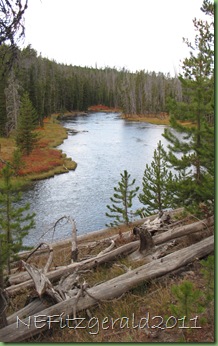

According to US Fish & Wildlife, Yellowstone’s Shoshone Lake is the largest backcountry lake in the lower 48 states that cannot be reached by a road. Early explorers to the area thought it flowed into the Madison River and so into the Atlantic Ocean. But in 1865 explorer and civil engineer Walter deLacy published his Map of the Territory of Montana with portions of the Adjoining Territories which showed “…hot springs at the head of an unnamed lake draining southward into “Jackson’s Lake” on the Snake River in present–day Grand Teton National Park. This unnamed lake was identified in 1867 as deLacy’s Lake and remained so until, a short time later, its name was changed to Shoshone Lake by a member of Hayden’s Geological Survey of the Territories.

|

| Shoshone Lake |

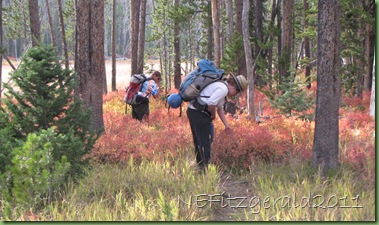

There are several routes into the lake – on this first of October day we choose to start at the Lewis Channel trailhead. This scenic seven – mile trail skirts the northern edge of Lewis Lake and then follows a channel connecting Lewis and Shoshone lakes. It is a fairly easy cruise, with minimal contouring up and down low hills along the water’s edge and nearly non-stop views.

|

| Lewis Lake with Teton Range in hazy distance |

|

| Mouth of Lewis Channel |

|

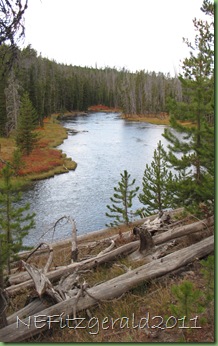

| Lewis Channel |

|

| Lewis Channel |

|

| Meandering trail along Lewis Channel |

We pause to watch kayakers and canoeists drift into view from upriver and then fade away downstream; we catch a fleeting glimpse (“What was that?”) of a short–eared owl as it silently streaks past our heads, seemingly low enough to snatch a hat or two in its talons. As the others relax, our angler feels the urge to drop his line in the water at a rocky outcrop. Further along the trail we graze on a few sweet huckleberries lingering at the end of their summer abundance. We are definitely not breaking any land–speed records on this leisurely afternoon trek.

|

| Canoeists paddle Lewis Channel |

|

| Relaxing on the rocks along Lewis Channel |

|

| Waiting for some action on Lewis Channel |

|

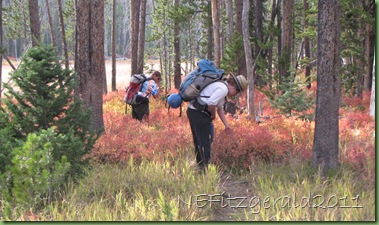

| Grazing an early October huckleberry patch |

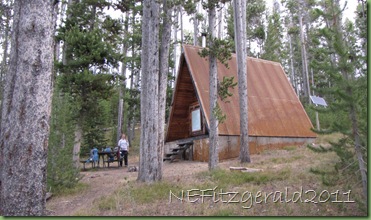

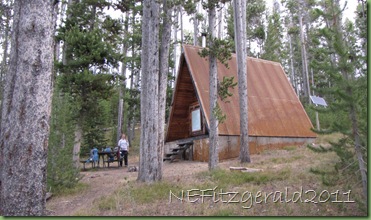

Eventually we reach the patrol cabin, an A–frame affair situated snugly at the edge of Shoshone Lake. We toast to our good fortune! We hope to see moose, we hope to see bears, we hope to see any wildlife besides a chattering ground squirrel unhappy with our intrusion into its domain.

|

| Shoshone Lake patrol cabin |

|

| View from the cabin porch |

|

| Cheers! |

What we do soon see is a fat brown trout on a line. Oh, yeah – dinner will be served!

|

| Dinner |

After our angler cleans his catch and sets it marinating in his secret blend of herbs, spices, and maple syrup, we all partake of that time–honored tradition of any lake visitor. We sit and watch the setting sun cast its golden glow behind low hills and gathering clouds. Then we go inside to enjoy our feast, have a nip while we play rummy by candlelight, and then fall cozily asleep, our mattresses arranged at tidy angles on the patrol cabin floor.

|

| Dinner awaits |

|

| Sunset over Shoshone Lake |

|

| Later that same evening… |

The next morning during a breakfast of tea and silver–dollar pancakes with huckleberry syrup we all comment on how this hike to Shoshone Lake is a perfect conclusion to our Yellowstone summer. We wash the dishes, re–hang mattresses on beams, sweep the floor, and lay a fire in the stove, aiming to leave the cabin in better condition than we found it. Then, in the drizzly gray of a misty morning we bid farewell to our final patrol cabin experience of the season and make our way four damp miles down the Dogshead trail back to our cars. We never do see a moose or a bear, but what we do see over the two days is exceptional.

|

| Leaving it cleaner than we found it |

|

| Red Mountains in the mist from Dogshead Trail |

Hey there, I'm Katherine Hanson, the curator of watchingforrocks.com, a site dedicated to uncovering the hidden gems of the USA. With a passion for exploration and a love for discovering the beauty in every corner of this vast country, I'm on a mission to share the best cities, national parks, historic landmarks, and entertainment hotspots that the USA has to offer. From towering mountains to bustling cities, there's so much to see and experience. Join me as I embark on adventures and uncover the wonders that make America truly remarkable.

Facebook / E-mail:

[email protected]

Life grabs hold where it can in Zion National Park, in the shadowy crevasses of the bleached–white cliffs and desert varnish–streaked walls of Navajo Sandstone, here and there dotted with aromatic ponderosa pine, gnarly Utah juniper, and lingering high–desert wildflowers. An unhurried ramble past Scout’s Lookout on the West Rim trail offers anyone who is interested a first-rate display of this resolute late–October life.

Life grabs hold where it can in Zion National Park, in the shadowy crevasses of the bleached–white cliffs and desert varnish–streaked walls of Navajo Sandstone, here and there dotted with aromatic ponderosa pine, gnarly Utah juniper, and lingering high–desert wildflowers. An unhurried ramble past Scout’s Lookout on the West Rim trail offers anyone who is interested a first-rate display of this resolute late–October life.