I was a bit wary about hiking on the Riddle Lake Trail yesterday, and my caution could be summed up in one exasperating word – mosquitoes. A serious candidate for the state bird of Wyoming, Yellowstone mosquitoes are persistent and plentiful during July. So I saturated myself in Herbal Armour and tried not to pass out from the enveloping citronella fumes permeating my every pore.

|

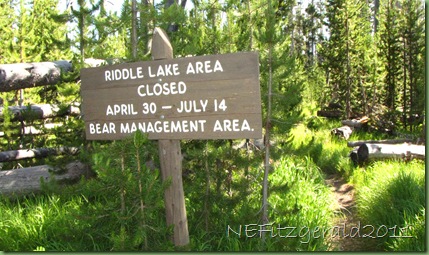

| Sign at Riddle Lake Trailhead |

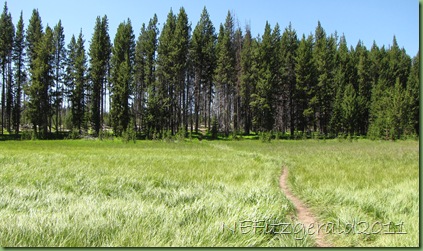

The 2.5 mile trail to Riddle Lake is quite level even though it crosses the Continental Divide at nearly 7,988 feet above sea level. It winds its pleasant way through towering lodgepole pine forest and across lush green meadows and marshland. The trail guide warns of mushy intermittent streams but the route was dry on this late July morning. Friday–hiking–buddy Sasha and I swatted at mosquitoes if we stopped moving, but soon a strong sweet breeze picked up and we were not bothered again for the rest of the hike.

|

| Lodgepole Pines on Riddle Lake Trail |

|

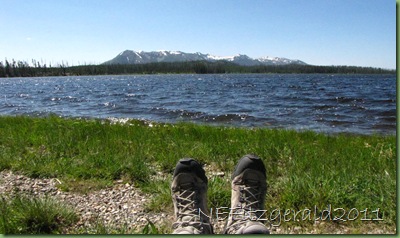

| View to Red Mountains from Riddle Lake trail |

|

| Red Mountains and Mt. Sheridan |

|

| Trail alongside Riddle Lake |

I took out my binoculars and scanned the shoreline, hoping to see a moose somewhere off in the distance. We perched ourselves on a lunch log and watched for half an hour or so while three graceful osprey soared overhead and then hovered with wings angled, calculating the precise moment and trajectory for a successful fish–catch in its talons. Soaring and diving, soaring and diving, the osprey went about their business untroubled by their audience. Bobbing white specks that turned out to be (trumpeter?) swans were only just visible in the water lilies on the far side of the lake.

|

| Feet with a Riddle Lake view |

We examined some grizzly bear tracks nearby – they seemed somewhat fresh but we could not tell if they were from five minutes ago or yesterday, and so we sang out “Hey bear!” anyway. Damselflies, butterflies, and a golden mantled ground squirrel devouring wildflower blossoms along the trail were much less threatening to our psyche as we ambled back to the car

There really isn’t much of obvious geologic interest here except the random cobble of obsidian. According to my geologic map, we cut across a small bit of the Aster Creek Flow of the Central Plateau Rhyolites but I could not discern it from any of the other detrital deposits we were walking upon. This is the Central Plateau of Yellowstone, on which the caldera that formed after the supervolcano explosion 640,000 years ago was filled in with subsequent lava flows. Many of these flows are hidden under the detritus of time.

I am still having a wild time trying to figure it all out.

|

| Elephanthead |

|

| Damselfly |

|

||

| Butterfly on either groundsel or goldenweed |

If there were one thing I could say about all the volcanic commotion that produced the wondrousness of Yellowstone National Park, it would be that it ain’t over til it’s over. For at least the past fifty million years there has been intermittent explosive volcanism of one sort or another in this region of the western US, and I expect that there will be more to come. Not in our lifetimes, perhaps, but then again you never know…

|

| Trail to lookout tower on Mt. Washburn |

|

| On the Mt. Washburn trail |

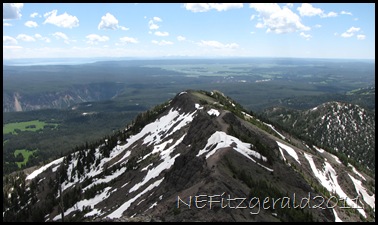

When some Utah friends visited earlier this month and wanted to hike the six–mile round-trip Dunraven Pass trail to Mt. Washburn lookout tower, I was more than happy to accompany them – this hike was definitely on my summer to–do list. At 10,243 feet above sea level it is one of the highest peaks in the park, offering jaw-dropping 360° views across the expansive Yellowstone caldera eastward towards the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone and the Absaroka Range, south through the haze to the Grand Tetons, and, outside the rim of the caldera, north to the Beartooth Mountains and northwest to the Gallatin Range. We would find ourselves on a lofty and very windy segment of the northern rim of the caldera.

|

| View from Mt. Washburn summit |

|

| Lunch with a view |

|

| Washburn Range |

All the guidebooks say that if you hike only one short trail in Yellowstone, make sure it is this one. What most of these guidebooks neglect to tell you, however, is that a goodly portion of the mountain was blown to infinity during either or both of the more recent Yellowstone supervolcano explosions – one at 2.1 million years ago and another at 640,000 years ago.

|

| Washburn Range |

|

| Crosscutting layers on Mt. Washburn |

Of the two main episodes of volcanism in the Yellowstone area, the Washburn Range Volcano in the north–central part of the park came into existence during an older period of volcanic activity that occurred in northwestern Wyoming 55–40 million years ago during the Eocene epoch. During this tectonically active time other volcanic fields were also formed – the Absaroka Range along the eastern side of the park, Bunsen Peak south of Mammoth Hot Springs in the northern part of the park, and intrusive igneous rocks of the southern Gallatin Range in the northwestern corner of the park.

Picture in your mind, if you will, the eruption in May 1980 of Mt. St. Helens with its lahars or mudslides flowing violently down the mountain slopes, and you will have a pretty good idea of what must have happened during eruptions of Mt. Washburn all those scores of millions of years ago. These lahars and later debris flows surged over the future Yellowstone and quickly enveloped any ancient forest that happened to be their path. In the nearby Specimen Ridge area, fossilized remains of sycamore, walnut, magnolia, chestnut, oak, redwood, maple and dogwood trees testify to a more temperate forest that was buried beneath this volcanic debris from Mt. Washburn. The angular conglomerate or breccia that is everywhere along the trail is evidence of the mudflows that poured off the mountain.

|

| Angular conglomerate or breccia |

|

| Angular conglomerate or breccia |

|

| Angular conglomerate or breccia |

|

| Angular conglomerate or breccia |

Absaroka volcanism occurred intermittently over several million years and ended around 40 million years ago, leaving a gently undulating volcanic plateau barely a few thousand feet above sea level and strewn with volcanic cones, of which Mt. Washburn was one.

Naturally, much geology happened in the intervening millennia but for now we must jump ahead to the Yellowstone of around 2.1 million years ago. BOOM!!! The first supervolcano explosion occurred at an unimaginably gigantic magnitude, blowing into oblivion nearly 600 cubic miles of subterranean magma chamber and overlying Rocky Mountains along with some fraction of adjacent Mt. Washburn. One and a half million years later BOOM!!! Another smaller yet still supervolcano explosion occurred in the same general area, blowing into oblivion yet another 240 cubic miles of magma chamber and any surrounding Rocky Mountains that happened to be left over from the earlier explosion. Because it is near the rim of the caldera it is most likely that at this time some fresh portion of Mt. Washburn again took a major hit. However, all the breccia I examined on the hike would be from the volcanism of 55–40 million years ago and not from the more recent supervolcano eruptions of the past 2.1 million years.

|

| Layered volcaniclastic rocks |

Bighorn sheep on the summit of Mt. Washburn

Bighorn sheep on the summit of Mt. Washburn View from the summit, Mt. Washburn****************************************Some Favorite Resources:

View from the summit, Mt. Washburn****************************************Some Favorite Resources:

Fritz, W.J., 1994, Roadside Geology of the Yellowstone Country

Lageson, D.R. and Spearing, D.R., 2009, Roadside Geology of Wyoming

Smith, R.B. and Siegel, L.J., 2000, Windows into the Earth – The Geologic Story of Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks

http://minerva.union.edu/hollochk/teaching_petrology/yellowstone_washburn.htm accessed 7/23/2001

I’m really trying to bring these blog posts back to geology topics. I was doing so well at the beginning! Since my arrival in Yellowstone Park back in mid–May, I’ve written about as many geyser basins and thermal features as I could manage to visit on my days off. I even have a few geologic adventures up my sleeve that are waiting to be written up. However, it’s crystal clear that I’ve been markedly distracted over these past few weeks. There is a lot of wildlife out there in the park, and I’m not talking about Uinta ground squirrels.

I simply had to try and see some wolves.

So last Thursday before my Utah visitors showed up, I arose at 5:20AM (on my day off!), inhaled a bowl of cold cereal, packed some snacks, my camera, binoculars and a camp chair, and with the sun hard in my eyes drove about 30 miles northward to Hayden Valley. By 7:00AM I had parked my car at Grizzly Overlook and was pretty much settled in for the long haul (or at least for the rest of the morning). This is prime wildlife–watching territory, and several hospitable wolf–watchers were already out and about with their spotting scopes and cheerful chit–chat. Many of these folks come year after year to watch the wolves in Yellowstone, often staying for weeks at a time and frequently returning later in the summer or even in the winter. They are not in the least interested in trying to approach close enough to the wolves for any sort of photograph but are content to use their scopes and binoculars from a mile and a half away. They recognize the packs from these distances, the alpha females and alpha males, their histories and their young pups. There is a wildlife ethic here among these wolf watchers that is palpable.

|

| Hayden Valley fog |

|

| Hayden Valley early morning |

We sat quietly in our camp chairs as the morning fog drifted along the Yellowstone River. Our murmured conversation was muffled across the thin morning air, as if not to disturb the enchantment of such a quiet time of day. The occasional motor home rumbled past, its occupants glancing out a window but not interested enough to stop and see what we were all about. Other park visitors and cars moved in and out of the periphery of our little core of wolf–watchers, some pausing to linger, and learn from the stories.

|

| Watching for wolves |

An hour passed. The fog gradually lifted and clouds shape–shifted, but not a wolf came into sight. I picked up my camera and binoculars and went for a walk atop a hillside across the highway. The wildflowers were just coming into blooming profusion, and I wondered idly if I might perhaps see a bear.

|

| Hayden Valley at Grizzly Overlook |

|

| Mountain dandelion |

|

| Silvery lupine |

I slowly made my way back to the overlook where I had staked out a little nest with my camp chair and tripod. I like my nifty little point and shoot camera, a Canon PowerShot SX10, and I know it doesn’t take spectacular photos from any sort of distance. None of that mattered. I am content to just know the wolves are there.

And then I thought I saw something moving. It seemed to steadily travel left to right, now visible, now hidden, up and down between the sagebrush–covered ridges and swales of the far side of Hayden Valley. “I think I see something. The sagebrush is moving.”

“Where?” they all asked excitedly, peering through their scopes.

“Between that sparse row of trees on the far left side of the river.”

And then we all soon saw the one, then a second, then a third gray wolf, all in a line, heading left to right towards what is known as Rendezvous Point far across Yellowstone River and Hayden Valley, where the dark tree line fades into the pale sagebrush flats and where the Canyon Pack does indeed often rendezvous. We watched them through binoculars and spotting scopes, threading their way to disappear behind the tree line.

For the next few moments I could only gaze into the distance where these wolves of Yellowstone had passed. A bit later someone noticed five wolves as they passed from right to left, away from Rendezvous Point, closer to the river’s edge this time but still riding the waves of pale dusky sagebrush. This was the Canyon Pack without its three new pups. I forgot to ask if the pups would have stayed by themselves while their mother went out hunting for dinner. Perhaps the pups were there with the rest of the pack all the time, hidden from sight by the thick sagebrush cover. I don’t know.

For the next two hours we sat and watched, but no more wolves made their presence known to us. I was meeting my friends from Utah that afternoon, and so around noon I headed back to Grant Village, the sun no longer hard in my eyes but my spirit content with a morning’s sightings of the Canyon Pack.

Some friends from Utah recently came to visit me in Yellowstone.

Oh, no, wait… This guy didn’t come from Utah to see me.

But these four did!

The route to our geologically amazing Friday hike took us north from Grant Village through Hayden Valley, and it was there that we all met some new friends. This particular time I was not driving through the bison jam but was a passenger, and so I got to hang out the window of the car and take lots of pictures.

These gracefully ginormous animals were going nowhere fast. We were caught in the jam for about 10 minutes, but soon Bison bison and all other creatures moved along to wherever they thought they needed to be going.

Since this is my first summer season at Yellowstone, I don’t have much of a frame of reference with which to compare past observations. But I must say there seems to be lot of water around this part of the Rocky Mountains.

|

| Courtesy USGS |

According to USGS real-time water data, as of July 9, 2011 there are 28,400 cubic feet per second (cfs) of Yellowstone River flowing near Livingston, MT, about 60 miles from Mammoth Hot Springs at the north entrance to the park. The maximum for the past 86 years was 21,300 cfs in 1975 while the minimum was 3000 cfs in 1931. The median cfs is 8,340 while the mean is 9,080. I am neither a hydrologist nor a statistics freak – is the average cubic feet per second of Yellowstone River somewhere between these two numbers or around 8,710 cfs?

|

| Yellowstone River at Fishing Bridge area |

|

| Fishing Bridge across Yellowstone River |

|

| Fishing Bridge steps to Yellowstone River |

Regardless, we are waaaaay over any of those numbers. In the park, swimming in the Firehole River is off-limits due to high water. Sections of roads are closed due to high water. Sections of trails are closed due to high water. Some lakeside boardwalks, notably at West Thumb Geyser Basin, are nearly submerged due to – you guessed it – high water.

The geese appear to be loving life in the submerged grasses!

|

| Canada Geese in Yellowstone River at Fishing Bridge area |

It will be fascinating to see if the lake level rises any more, and to watch as it recedes over the course of the rest of the summer.

|

| Submerged hot spring, West Thumb Geyser Basin, Yellowstone Lake |

|

| A rare close-up for a kayaker at West Thumb Geyser Basin |

|

| High-water Yellowstone Lake at West Thumb Geyser Basin |

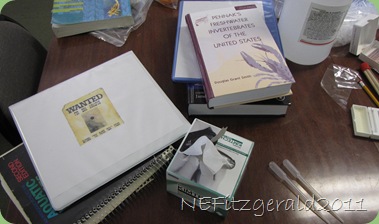

Today (my day off!) I had a chance to spend a few hours with a summer class from Montana State University’s Institute of the Environment, formerly Big Sky Institute. Science teachers from around the country had come to MSU for a week-long course in Yellowstone Lake Ecology. Yesterday they had come to the park to wade through Pelican and Arnica creeks, collecting water samples in containers and not a few leeches on themselves. Today they were in a make-shift lab, trying to identify all sorts of creepy-crawly freshwater invertebrates under the microscope. I was content to be participating today, not having had to endure the leech-fest yesterday. Totally gross!

Being geologically inclined towards the metamorphic variety, I was really out of my element with all these freshwater macro-invertebrates. Plus I was not taking the class – we had been invited to just hang out and learn something about lake ecology. But I was able to peek at some cool slides, which is always fun. I saw diatoms, mayflies, water fleas (Cladocerans), damselfly larva, caddis flies, midge larvae, cyanobacteria (Nostoc), and several different copepods. I have no idea what these organisms were supposed to look like under the microscope but I take great notes and so took names.

Being geologically inclined towards the metamorphic variety, I was really out of my element with all these freshwater macro-invertebrates. Plus I was not taking the class – we had been invited to just hang out and learn something about lake ecology. But I was able to peek at some cool slides, which is always fun. I saw diatoms, mayflies, water fleas (Cladocerans), damselfly larva, caddis flies, midge larvae, cyanobacteria (Nostoc), and several different copepods. I have no idea what these organisms were supposed to look like under the microscope but I take great notes and so took names.

Whenever folks found something intriguing in their water samples, they used a mountain of reference material to “key out” organisms down to the genus and hopefully the species level. They were even looking for amoebas but I do not know if anyone found one. I heard no “Eureka! An amoeba!” from the assembled class members.

The ultimate goal of the Institute’s Lake Biodiversity Project is to extract DNA from different organisms in order to identify them as far as possible (genus and hopefully species) and compare each to other DNA sequences for known or new Yellowstone Lake species.

Interestingly, a method for copying DNA was developed from a thermophilic (heat-loving) bacterium called Thermus aquaticus. It was isolated in the late 1960s from the clear, scalding waters of one of Yellowstone’s thermal features named Mushroom Pool. The PCR method of copying DNA requires a heat-stable enzyme, which is found in Thermus aquaticus (or Taq for short. Mass production of Taq revolutionized biological research; PCR is now the most widely used method for studying DNA in biotechnology, molecular biology, medical research, and law enforcement laboratories around the world.

Actually, that title is slightly misleading. I didn’t really begin to decipher this whole volcanic rhyolite lava thing that’s on the ground in Yellowstone until a couple days after my hike to Fairy Falls last week. It must have been seeing that osprey hovering intently above the Firehole River that set me off to thinking.

Or perhaps it was the dragonfly perched in the pine.

Could it have been the frog nestled in the marsh grass?

It might have been the bison, off in the distance…

It might have been the bison, off in the distance…

Or maybe it was the marsh wren singing in the tree?

This slender blue creature surely had something to do with my “Aha!” moment.

What are these Yellowstone rocks? As I glanced back at Fairy Falls tumbling off the volcanic cliffs, I was determined to discover an answer.