My high-country neighborhood is draped beneath several inches of snow. Another storm had been predicted to blow into southwestern Utah this weekend. It crept in almost imperceptibly, without the roaring winds and pea-sized hail and sideways-blowing snow of last week.

Saturday skies turned slowly gray and overcast as the afternoon wore on; overnight the snow fell silently and without fuss. Sunday it has fluttered and fallen steadily throughout the mid-afternoon with little sign of letting up.

Saturday skies turned slowly gray and overcast as the afternoon wore on; overnight the snow fell silently and without fuss. Sunday it has fluttered and fallen steadily throughout the mid-afternoon with little sign of letting up.

|

| Juniper berries |

|

| The tomato patch waits for springtime |

|

| Aspen leaves |

|

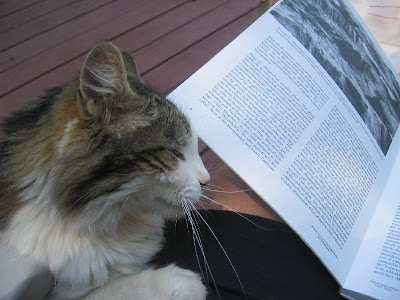

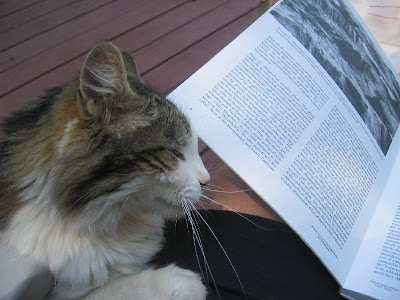

| Pink Floyd has been through many Utah winters |

|

|

|

An adventure in Watching for Rocks can be anything you want it to be. It can involve exotic geologic destinations and months if not years of planning. You can devote endless hours perusing cheap-flight websites, we-be-the-best-deal car rentals, and hope-this-isn’t-a-fleabag-motel-dot-com until you start hyperventilating with excitement. Or, you can merely slip on a jacket, grab your camera, and talk a walk in any old nearby neighborhood. If you live where the rock outcrops are exposed and there isn’t all that pesky vegetation to obscure them, so much the better. Otherwise, you might consider bringing along a machete.

An adventure in Watching for Rocks can be anything you want it to be. It can involve exotic geologic destinations and months if not years of planning. You can devote endless hours perusing cheap-flight websites, we-be-the-best-deal car rentals, and hope-this-isn’t-a-fleabag-motel-dot-com until you start hyperventilating with excitement. Or, you can merely slip on a jacket, grab your camera, and talk a walk in any old nearby neighborhood. If you live where the rock outcrops are exposed and there isn’t all that pesky vegetation to obscure them, so much the better. Otherwise, you might consider bringing along a machete.

Nearly every square foot of southern Utah’s geology, generally unhindered by that pesky vegetation, has been examined over the past hundred years or more by tens of thousands of people on foot, on horseback, by boat, in autos, in airplanes, and remotely by satellite. A couple of years ago an interim geologic map of the St. George area was published and I became the proud owner of a copy – included are page after page of descriptions of all the mapped stratigraphy including that of the hills behind where I live. I remain delirious whenever I have cause to study this colorful map.

I don’t know how many readers of WATCH FOR ROCKS know how to read a geologic map. It isn’t that difficult, really; once you figure out that the top layer on some particular patch of ground is the one that is represented on your particular section of map, you’ve got it made in the shade. However, applying the map scale to what you see on the ground can be a bit of a sticky wicket. Trying to find the hill behind your house on a map with a scale of 1:100,000 (≈5/8 inch on the map equals ≈ 1 mile on the ground) is just slightly less difficult than trying to pronounce Eyjafjallajäkull volcano.

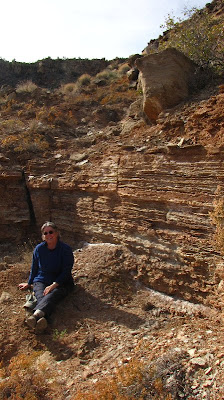

I discovered that these are volcanic rocks on the hills immediately behind where I live, and two low hills are mapped as two distinct units: the Quichipa Group and the Condor Canyon Formation. These are mainly tuffs, or cemented volcanic ash. Their age dates range from the late Oligocene Epoch (≈26-23 million years ago) to the early Miocene Epoch (≈23-16 million years ago). These rocks tell of violent volcanic eruptions which produced immense quantities of ash and rubble that were blown across eastern Nevada and western Utah.

I discovered that these are volcanic rocks on the hills immediately behind where I live, and two low hills are mapped as two distinct units: the Quichipa Group and the Condor Canyon Formation. These are mainly tuffs, or cemented volcanic ash. Their age dates range from the late Oligocene Epoch (≈26-23 million years ago) to the early Miocene Epoch (≈23-16 million years ago). These rocks tell of violent volcanic eruptions which produced immense quantities of ash and rubble that were blown across eastern Nevada and western Utah.

How immense? Some of the individuallayers of ash (and there were plenty of them in the 7 million years spanning the late Oligocene to early Miocene), representing a single volcanic blast, can be traced across areas of nearly 15,000 square miles. These sheets of ash are fairly uniform in character and so can be traced with little difficulty across vast areas.

How immense? Some of the individuallayers of ash (and there were plenty of them in the 7 million years spanning the late Oligocene to early Miocene), representing a single volcanic blast, can be traced across areas of nearly 15,000 square miles. These sheets of ash are fairly uniform in character and so can be traced with little difficulty across vast areas.

As material is deposited on the earth, such as happened with our ash layers, the iron and other magnetic minerals in the layers are aligned in the same direction as the earth’s magnetic field. Scientists discovered decades ago that the earth’s magnetic field has reversed periodically in the past – the magnetic poles of north and south were switched or “flipped.”

In the Condor Canyon Formation mentioned above there is a layer of ash called the Swett Tuff member. If you happen to find yourself standing, say, 20 yards or more away from this Swett Tuff while holding a good compass, the needle will point north as expected. But move ever so slowly closer and closer to the Swett Tuff and your compass needle will start to quiver. Keep moving closer, and closer, and closer until you are within inches of the tuff at which point your compass needle will have flipped. Your compass needle will now be pointing to the south.

I had hoped that this Swett Tuff would show up as an outcrop in the hills behind where I live. Sadly, it does not. I know where to find it, though, and the location isn’t very far away. I need to get back there to see it again; the magnetic reversal it displays is nothing short of astonishing.

Note: Utah Geol. Survey Open-File Report 478 was my source for map information. “The Broken Land – Adventures in Great Basin Geology” by Frank L. DeCourten was my source for information on Oligocene and Miocene tuffs. I refer to it often and recommend it highly. The top six:United States – 4,553Germany – 1,845Barbados – 219 Russia – 154United Kingdom – 131Netherlands – 102

|

| Even some cats like it when I read to them about geology! |

And in decreasing numbers, in noparticular order:Spain- 1India – 53Canada – 48China – 39Croatia – 1Turkey – 1Philippines – 1Australia – 17South Korea – 2Malaysia – 2France – 8Greece – 8Slovenia – 10Japan – 44Kenya – 1

According to the Blogger stats, as of this morning people from all of these countries have visited my blog. The numbers display how many hits have come from each country. This is so amazing and totally cool! Each time I check the stats for the past day, week, month, and all-time, I get all goose-bumpy seeing so many countries represented.

Naturally I would expect the United States to show the most hits, but Barbados? Third? This is stunning information. And The Netherlands, UK, Germany, Russia – you rock!!! The “no particular order” list is also intriguing – Slovenia? Turkey? Kenya??? I am impressed. In fact, I am impressed by all the countries. Welcome to my world!

These stats have been calculated since I started the blog, whereas the cute little world map on the left (the widget below “Blogs I Enjoy”) has just been counting hits for the few weeks since I inserted it. BTW – you should be able to click on this map and it should show individual countries on each continent. In addition, I do not track my own pageviews so as to get as accurate a count as possible. Too much fun!!!

When I started writing WATCH FOR ROCKS this spring I was heading off to Alaska to work at Katmai National Park for the summer. Like many others who decide to launch themselves into the blogosphere, I initially wrote for my family and friends so that they could keep up with my adventures; through me, they could travel vicariously to a location most would likely never be able to experience in person. They were jazzed that I would be writing a blog and quickly signed up as Followers. I had no idea how this all would play out, or whether anyone would be interested after I left Alaska and came back home to Utah.

Seven months later, readers from all over the world keep discovering WATCH FOR ROCKS. During that time I have met up with folks who had googled “Katmai” as they were planning their trips and my blog popped up (those keywords typed in at the bottom of each post aren’t there for nothing!). Others I have met along the way as our paths crossed serendipitously, viewing bears at Brooks River or backpacking in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes; I wrote my blog address on a slip of paper and encouraged people to join the adventure as they continued along on their own journeys. Still others found my blog through a link on another website.

Although I personally know quite a few of the readers of my blog (Followers or not), I have never met many others and perhaps never will. I do sincerely hope you continue reading and enjoying my blog. I am thrilled that you are intrigued enough by what I have to say to keep coming back and wish I could meet you all.

A couple days ago my sister helped me print WATCH FOR ROCKS business cards. I am now on my way to the stratosphere of the blogosphere – no longer will I have to scramble for scraps of paper or bar napkins on which to scribble my blog address. I have even handed out a few already.

Woo Hoo!!! Imagine yourself on a vast featureless coastal plain, with geographic relief in every direction of only a few centimeters as far as the eye can see. It is an arid environment, with negligible rainfall for at least decades if not centuries at a time. High temperatures bring an attendant high rate of evaporation, and there is little vegetation to give ease to the eye from the bleak whiteness of the terrain (plus you forgot your sunglasses). Since it is a coastal plain, an occasional storm at sea might blow in to submerge the plain ever so slightly, barely covering your toes as you stand there, and bringing with it a thin deposit of carbonate mud. But nearly as soon as any water appeared it would retreat back to sea or evaporate, leaving with its disappearance another thin crust, a crust of precipitated minerals which uniformly cover the mud.

You would be forgiven for thinking you were on the coast of the Persian Gulf today – but it is likely you could also be standing in a Utah landscape of 240 million years ago. If you stood on this coastal plain for five million years (don’t forget a hat and sunscreen), not much of anything else would happen beyond a seemingly endless cycle of thinly deposited layers of mud and evaporites, mud and evaporites.

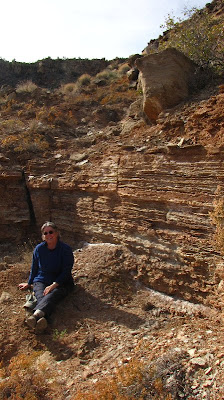

|

Moenkopi Formation of

Grafton Mesa |

We can see all this in the rocks of the Moenkopi Formation which outcrops all over southern Utah. A great place to get nose-close to the upper two members of this Formation, the Shnabkaib and the Upper Red, is along the trail to Grafton Mesa near Rockville and Zion National Park.

|

| Gypsum of Shnabkaib member along Grafton Mesa trail |

|

| White gypsum and red mudstone layers of Moenkopi Formation |

|

|

|

In the lower Shnabkaib member, gypsum was deposited in a “sabkha” or salt flat environment from evaporation of ocean or marine waters. The Upper Red consists of siltstone, mudstone, and sandstone deposited in arid tidal flats and coastal plains. Eventually, around 220 million years ago the environment changed to continental sediments of shallow interconnected braided streams. These streams drained into Utah from highlands of what would one day become Texas. We can see this in the sandstones and conglomerates of cliffs overlying the Moenkopi.

|

| Contact between Moenkopi and overlying cliffs |

|

| Gypsum beds |

It should come as no surprise that when I hike these days I stop pretty much every few feet to look at the rocks. Friends who hike with me are used to this; they will listen patiently as I blather on about sea level advances and retreats and the roundness of quartzite pebbles in conglomerates. Since we are not intent on breaking any land-speed records anyway, a three-mile round trip hike to the top of Grafton Mesa and back can take six hours if we are lucky!

|

| Judy perched on a conglomerate towards the top of Grafton Mesa |

|

| Moenkopi Formation in foreground; Navajo Sandstone cliffs of Zion NP in distance |

|

| Petrified wood fragments scattered in quartzite pebbles on top of Grafton Mesa |

|

| Lichen on sandstone |

According to my last post, I’ve been to the Burgess Shale twice and on one of those treks volunteered as a guide on hikes to the Walcott Quarry and Mt. Stephen fossil beds. I’ve hiked on the Athabasca Glacier – across barely a miniscule square-mile area of a San Francisco-sized chunk of Rocky Mountain ice, but it was a glacier nevertheless. I’ve backpacked in Katmai National Park to Novarupta, the 1912 site of the world’s largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century. What’s the next item on my Geological Bucket List? I have been warned that as long as I don’t use the word “uber” anymore, there are quite a few possibilities.

First things first. I’ve really got to experience more of my own geological backyard before venturing any further. Ninety miles away from where I live there exists this really big hole in the ground with a river running through it that begs for my attention. I’ve hiked on the rim and backpacked down into Grand Canyon but have never floated through it on the Colorado River.

Wait a minute! exclaims MY TRAVEL AGENT innocently. Don’t I want to float the entire river? He could arrange for that, he says nonchalantly, from the source at swampy La Poudre Pass Lake high on the continental divide in Colorado, all the way to some vague location past the Salton Sink and the desiccated wasteland that is the 21st century’s mouth of the mighty river. He’d route me to find Mexico and the Sea of Cortez somehow. Wouldn’t I want to do the whole enchilada?

|

| Colorado River below Glen Canyon Dam |

Mmmm… Probably not. Too many logistics. Running the Colorado River in Grand Canyon National Park is what I’ve had in mind for a long time. My GBL trip would be a 14-day hybrid oar-and-paddle trip for the distance of 226 river miles from Lee’s Ferry below Glen Canyon Dam to Diamond Creek above Lake Mead. I want to savor floating serenely and paddling manically through geologic time, through nearly two billion years of Earth history, down, down, down into the crystalline basement rocks of narrow Granite Gorge of the Inner Canyon, into rocks that are first cousins to schists and gneisses found in the Beaver Dam Mountains of southwestern Utah.

For now, I’d like to think I’m not finished in Canada – one totally accessible target on my GBL is Cape Breton Highlands National Park in Nova Scotia. Its Cape Breton Plateau plastered across the northeastern tip of this Maritime Province could surely make me weep tears of ecstasy – they are the exposed roots of the Appalachian Mountains, formed 360-325 million years ago during tectonic collisions between ancient Europe and North America.

However, one big-dream GBL entry may be more dream than reality since what I have in mind would be monumentally more difficult to attain than rafting Grand Canyon and would cost even more buckets-full of cash. Some of the oldest intact rock units on the planet can be found in Canada and here lies my big-dream GBL. To get to the Acasta Gneiss (4.03 billion years or so old) I merely have to get to Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories (Salt Lake City to Calgary to Yellowknife – I have looked into this!), then charter a bush pilot to take me 300 km north onto the Slave Craton near Great Bear Lake, and then find a certain obscure island in the middle of the obscure Acasta River…

Nothing can keep me from my dreams.

These are only a few entries on my Geological Bucket List. Leave a comment and let me know of yours!

|

| Novarupta plug in right foreground, Trident volcano in background |

|

| Sockeye salmon moving up Brooks River |

|

| Sockeye salmon in Brooks River |

|

| Brown Bear along Naknek Lake |

Travel has always been at the top of my personal agenda – I travel as much as my vacation time and disposable cash flow will allow. The best of both worlds occurs when I can travel and work, getting paid to be somewhere with a geological twist. Serendipity finally brought me to Katmai National Park in Alaska this past summer where I worked as a ranger for the national park service from early May until mid-September. Novarupta volcanism, sockeye salmon, and brown bears – did my Alaska adventure really happen or did I dream it?

But like most everyone else, I also have been forever imagining myself in places to which I would travel if I had no limits but had all the time and money in the world. Since I am fairly confident that at least one of those pesky limits will be present to torture me at any given time (I have plenty of time right now but I’m certainly not getting any younger; as for cash – well, I definitely don’t like leaving home without it), my own personal “bucket list” consists of locations where I can reasonably expect to find myself one day.

Of course, these sites would have to involve geology – ancient rocks, jaw-dropping formations, tectonic plates colliding, extraordinary fossils. All I need now is to find an uber-billionaire to underwrite my expeditions or to convince Nat Geo to hire me as a travel writer – and I’ll be on my way.

|

| Burgess Shale, Yoho National Park, British Columbia |

I started working on my GBL (Geological Bucket List) in 2005. I had been planning an adventure in northern Spain for autumn 2004 – this early pre-geology Bucket List entry included visiting some cave painting sites (remnant yearnings from my first college degree in anthropology but that’s another story), seeing the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao, and then doing a 12-day trek in the Picos de Europa mountain range of northern Spain. Unfortunately for me this trip never materialized – I was in the throes of leaving my 20-year nursing career to go back to school and get my degree in geology and could not manage to fly away to another continent. So when I had to cancel this trip of a lifetime to Spain, I knew exactly what I’d do instead. I’d go to Canada. I’d hike to the Burgess Shale fossils, high in the Rocky Mountains of Yoho National Park, British Columbia. It seemed like a great place to start checking off entries on my GBL.

|

| At Walcott Quarry |

“Exquisite” is the word most often used to describe the preservation of the 505-million-year-old fossils of the Burgess Shale, and I wanted to see them in a bad way. Ancestors of virtually all life forms on Earth today can be found preserved in these rocks, in the hard shells and soft body parts of creatures such as Pikaia, Anomalocaris, Halucigenia, Opabinia, Marrella, Canadaspis, and the trilobites Ogygopsis and Elrathia. Though not in the same abundance or state of preservation, many of these same fossils have been found in similar rocks of western Utah and eastern Nevada, particularly in the Pioche and Wheeler Shales and Marjum Formation.

|

| Icefields Parkway, Jasper NP |

Not many people I know have been to the Burgess Shale. I have been there twice – first in 2005 and again in 2008 when I returned as a Volunteer Assistant Guide on the hikes to the Walcott Quarry and Mt. Stephen fossil beds. The sites are part of the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks UNESCO World Heritage Site. My two dear San Diego friends accompanied me both times under no duress whatsoever. The second time we explored further beyond Yoho NP into the uplifted structural geology wonderland of the Icefields Parkway.

Should hiking on the Athabasca Glacier also count as a check-off on my GBL?

Hey there, I'm Katherine Hanson, the curator of watchingforrocks.com, a site dedicated to uncovering the hidden gems of the USA. With a passion for exploration and a love for discovering the beauty in every corner of this vast country, I'm on a mission to share the best cities, national parks, historic landmarks, and entertainment hotspots that the USA has to offer. From towering mountains to bustling cities, there's so much to see and experience. Join me as I embark on adventures and uncover the wonders that make America truly remarkable.

Facebook / E-mail:

[email protected]

Saturday skies turned slowly gray and overcast as the afternoon wore on; overnight the snow fell silently and without fuss. Sunday it has fluttered and fallen steadily throughout the mid-afternoon with little sign of letting up.

Saturday skies turned slowly gray and overcast as the afternoon wore on; overnight the snow fell silently and without fuss. Sunday it has fluttered and fallen steadily throughout the mid-afternoon with little sign of letting up.

An adventure in Watching for Rocks can be anything you want it to be. It can involve exotic geologic destinations and months if not years of planning. You can devote endless hours perusing cheap-flight websites, we-be-the-best-deal car rentals, and hope-this-isn’t-a-fleabag-motel-dot-com until you start hyperventilating with excitement. Or, you can merely slip on a jacket, grab your camera, and talk a walk in any old nearby neighborhood. If you live where the rock outcrops are exposed and there isn’t all that pesky vegetation to obscure them, so much the better. Otherwise, you might consider bringing along a machete.

An adventure in Watching for Rocks can be anything you want it to be. It can involve exotic geologic destinations and months if not years of planning. You can devote endless hours perusing cheap-flight websites, we-be-the-best-deal car rentals, and hope-this-isn’t-a-fleabag-motel-dot-com until you start hyperventilating with excitement. Or, you can merely slip on a jacket, grab your camera, and talk a walk in any old nearby neighborhood. If you live where the rock outcrops are exposed and there isn’t all that pesky vegetation to obscure them, so much the better. Otherwise, you might consider bringing along a machete. I discovered that these are volcanic rocks on the hills immediately behind where I live, and two low hills are mapped as two distinct units: the Quichipa Group and the Condor Canyon Formation. These are mainly tuffs, or cemented volcanic ash. Their age dates range from the late Oligocene Epoch (≈26-23 million years ago) to the early Miocene Epoch (≈23-16 million years ago). These rocks tell of violent volcanic eruptions which produced immense quantities of ash and rubble that were blown across eastern Nevada and western Utah.

I discovered that these are volcanic rocks on the hills immediately behind where I live, and two low hills are mapped as two distinct units: the Quichipa Group and the Condor Canyon Formation. These are mainly tuffs, or cemented volcanic ash. Their age dates range from the late Oligocene Epoch (≈26-23 million years ago) to the early Miocene Epoch (≈23-16 million years ago). These rocks tell of violent volcanic eruptions which produced immense quantities of ash and rubble that were blown across eastern Nevada and western Utah. How immense? Some of the individuallayers of ash (and there were plenty of them in the 7 million years spanning the late Oligocene to early Miocene), representing a single volcanic blast, can be traced across areas of nearly 15,000 square miles. These sheets of ash are fairly uniform in character and so can be traced with little difficulty across vast areas.

How immense? Some of the individuallayers of ash (and there were plenty of them in the 7 million years spanning the late Oligocene to early Miocene), representing a single volcanic blast, can be traced across areas of nearly 15,000 square miles. These sheets of ash are fairly uniform in character and so can be traced with little difficulty across vast areas.